Lesson 1: The Evolution of Money and Trust

Lesson 1: The Evolution of Money and Trust

🎯 Core Concept: Money as a Ledger Technology

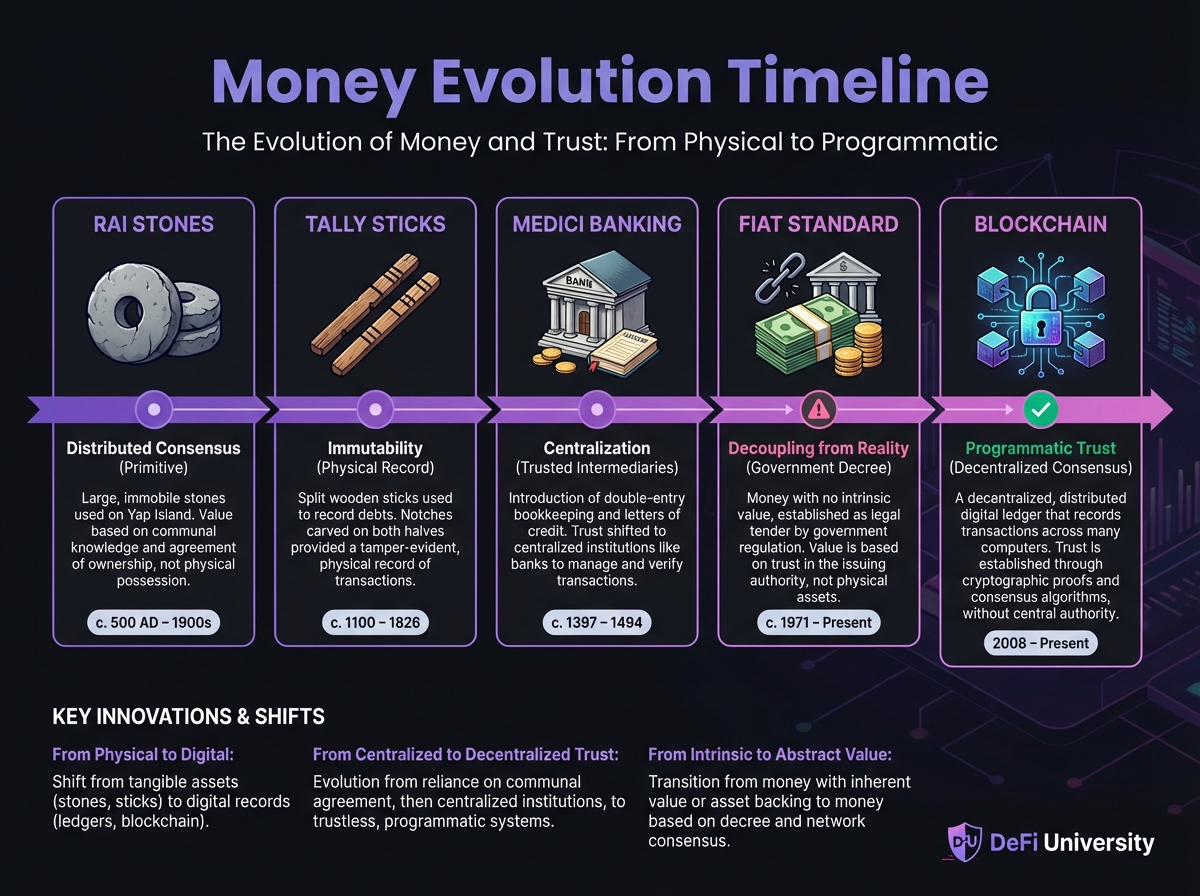

Money is frequently misunderstood as a commodity—a shiny metal or a printed piece of paper. However, a rigorous historical analysis reveals that money is, and always has been, a system of accounting. It is a technology for recording debts and credits, a mechanism for social memory. The history of finance is, therefore, the history of the ledger: the record of who owes what to whom.

The evolution of this technology—from oral tradition to wood, to paper, and finally to code—reflects humanity's ceaseless struggle to solve the problem of trust at scale. Understanding this evolution is essential to comprehending why blockchain and DeFi represent such a fundamental shift.

📚 The Historical Evolution: From Rai Stones to Bitcoin

The Stone Ledgers of Yap: The Progenitor of Distributed Consensus

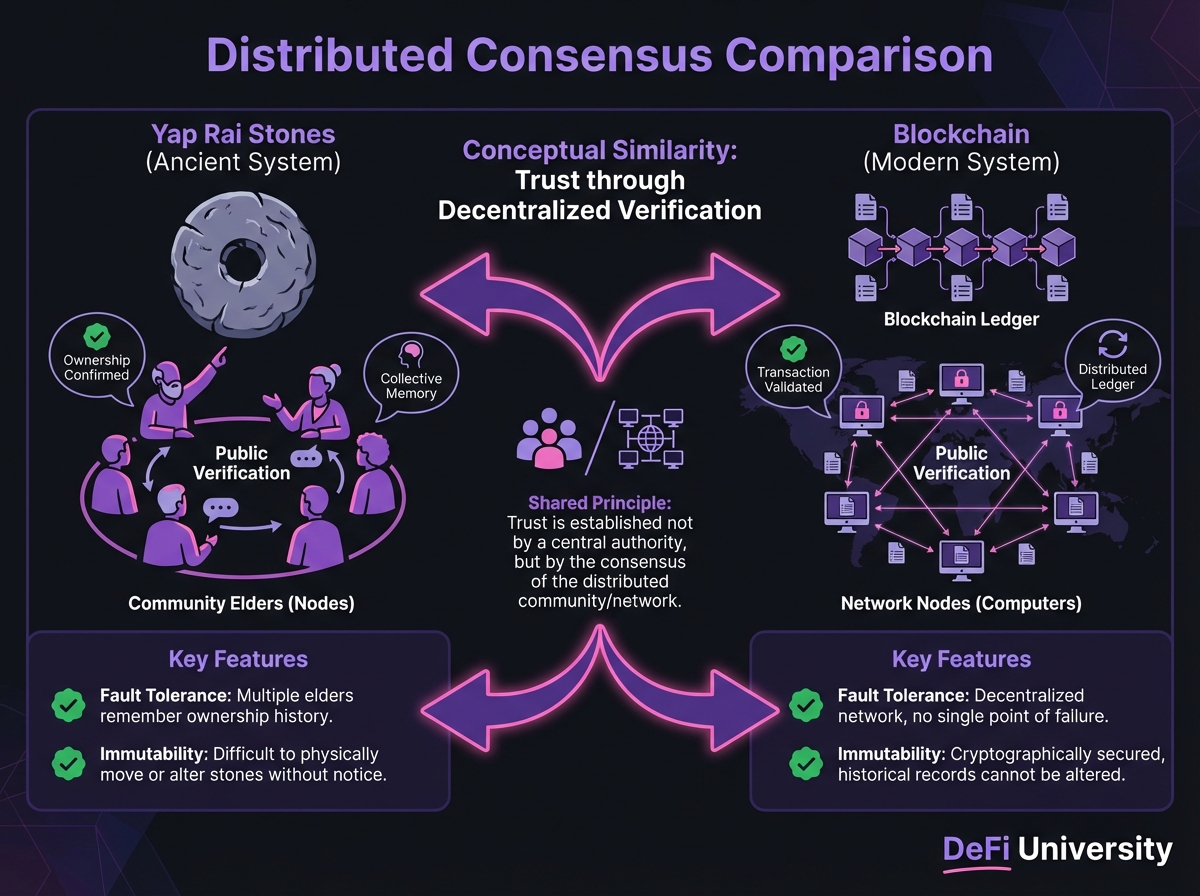

Long before the advent of digital cryptography, the indigenous people of the Yap islands in Micronesia developed a monetary system that conceptually mirrors the architecture of modern Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT). This system, centered around the Rai stones, challenges the conventional economic narrative that money must be portable, divisible, and fungible to function.

The Rai were massive limestone discs, quarried on the distant island of Palau and transported to Yap by canoe. The largest of these stones stood up to 12 feet tall and weighed approximately four tons. Their sheer physical immobility necessitated a profound conceptual leap: the separation of possession from ownership.

In most monetary systems, to transfer value, one must physically transfer the token (the coin or bill). In Yap, the token often remained stationary. When a transaction occurred—such as a wealth transfer for a marriage dowry, land rights, or political alliance—the physical stone was not moved. Instead, the transfer of value was effectuated through a mechanism of social consensus that functioned remarkably like a modern distributed database.

The community elders would gather at the site of the stone or in a public forum. The transaction would be announced, and the transfer of ownership from Party A to Party B would be publicly ratified.

This process exhibits the core properties of a blockchain:

Distributed State: The "ledger" of ownership was not held in a central bank vault or a single king's scroll. It was distributed across the minds of the community elders. Each elder acted as a "node" in the network, maintaining a mental record of the current state of ownership for every stone on the island.

Public Verification and Consensus: Transactions were public events. This transparency prevented the "double-spending" problem; one could not secretly sell the same stone to two different people because the community consensus—the distributed ledger—would reject the invalid transaction.

Fault Tolerance and Redundancy: If one elder died or forgot a detail (analogous to a node going offline or a hard drive failing), the integrity of the ledger was preserved by the collective memory of the remaining elders. The system was resilient to single points of failure.

The Sunken Stone: The abstraction of value in the Yapese system reached its zenith in a famous historical anecdote. A particularly magnificent Rai stone was being transported back to Yap when a severe storm struck the canoe. To save their lives, the crew cut the stone loose, and it sank to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Upon returning to the island, the crew testified to the stone's existence and its immense size. The community elders convened and deliberated. They reached a consensus: the accident was not the fault of the owners, and the stone still existed, even if it was physically inaccessible. The "ledger" was updated to reflect that the family still owned the stone, and its value continued to circulate in the Yapese economy for generations, used to settle debts and transfer wealth, despite the fact that the physical asset was sitting on the ocean floor.

This is conceptually identical to a digital asset on a blockchain. A Bitcoin does not exist as a physical object; it exists as an entry on a distributed ledger agreed upon by the network. The physical location of the mining servers is irrelevant to the validity of the value, just as the location of the sunken Rai stone was irrelevant to its purchasing power.

Tally Sticks: The Immutable Hardware of Debt

While the Yapese relied on oral consensus and social reputation, medieval Europe developed a hardware-based solution to the problem of trust: the split tally stick. Emerging in a time of widespread illiteracy and scarce coinage, the tally stick became the primary instrument for recording debts, tax obligations, and commercial contracts in England and across Europe for over seven centuries.

The Mechanism: A hazelwood stick was inscribed with notches indicating the amount of a debt or tax payment. The width of the notches corresponded to specific values: a palm's width for £1,000, a thumb's width for £100, and so on. Once the transaction was recorded, the stick was split lengthwise down the middle, creating two distinct halves:

The Stock: The longer half, given to the lender or the party to whom money was owed. This represents the origin of the financial term "stockholder"—one who holds the physical proof of a debt or investment.

The Foil: The shorter half, given to the debtor or the party who had received the funds/goods.

The Security: The security of the tally stick system lay in the unique, erratic grain of the natural wood. Much like a biometric fingerprint or a modern cryptographic hash function, the two halves of the stick would only fit perfectly with each other. This physical property made the system resistant to counterfeiting and fraud. If the debtor tried to whittle away notches on their foil to lower their debt, the halves would no longer align upon reunification. If the creditor tried to add notches to the stock to inflate the debt, the fraud would be instantly visible.

The tally stick was, in essence, an immutable, tamper-evident distributed ledger where each transaction was recorded on a unique hardware device held by the counterparties.

The End of Tally Sticks: The end of the tally stick era had a symbolic and fiery conclusion that underscores the dangers of centralized storage. In 1834, the British Exchequer finally decided to retire the system and ordered the burning of centuries of accumulated tally sticks. The sticks were fed into the furnaces beneath the Houses of Parliament. The blaze grew so intense that it overheated the flue systems, igniting a fire that consumed the entire Palace of Westminster. The destruction of the Houses of Parliament by the burning of the old financial ledger serves as a potent metaphor for the transition from the era of physical, decentralized artifacts to the volatile era of centralized paper records.

The Medici Revolution: The Centralization of Trust

The transition from the localized, bilateral trust of tally sticks to the globalized financial system we recognize today began in Renaissance Italy with the Medici family. Before the Medici, banking was a fragmented, high-risk endeavor limited by the dangers of physical travel. The innovation that propelled the Medici Bank to become the most powerful institution in Europe was not merely financial; it was a revolution in information architecture centered on the centralization of trust.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping: The Medici popularized Double-Entry Bookkeeping, a system codified by Luca Pacioli in 1494. This system ensures that every transaction is recorded twice—once as a debit and once as a credit—ensuring that the books always balance:

Assets=Liabilities+Equity

This methodology provided a standardized, internal error-checking mechanism that allowed the Medici to manage a complex, multi-national empire with unprecedented precision.

The Letter of Credit: However, the true genius of the Medici was in decoupling value transfer from the movement of physical assets through the Letter of Credit. In the medieval world, traveling with chests of gold was an invitation to robbery and murder. The Medici solution allowed a merchant to deposit florins at the Medici branch in Florence and receive a paper letter—a cryptographic-like claim check. The merchant could then travel to London, present the letter to the Medici branch there, and withdraw the equivalent value in pounds or ducats.

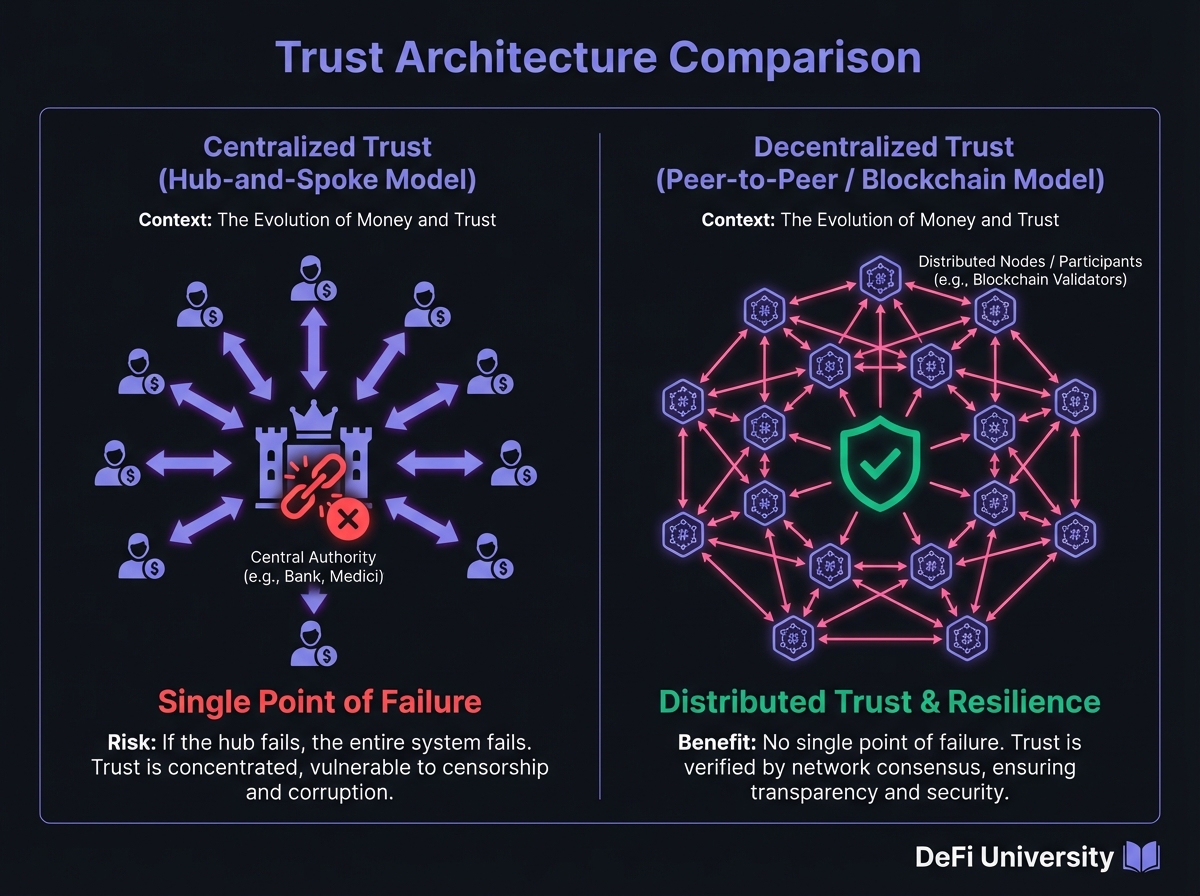

The Hub-and-Spoke Architecture: This innovation marked a profound shift in the topology of trust:

From Bilateral to Centralized: With tally sticks, trust was between the two parties holding the wood. With the Letter of Credit, the merchant in London did not need to trust the merchant in Florence; they only needed to trust the Medici Bank. The bank became the "Trusted Third Party," the universal intermediary.

The Hub-and-Spoke Model: The Medici Bank operated as a holding company with a centralized headquarters in Florence and semi-independent branches (spokes) in major commercial centers. This structure allowed them to ring-fence risk—if the London branch failed, it would not necessarily bankrupt the Florence hub—but it fundamentally centralized the "truth" of the ledger within the Medici family's control.

While efficient, this model introduced a Single Point of Failure: if the central ledger was corrupted, or if the family's governance failed, the entire network of trust could collapse.

The Fiat Standard: Decoupling from Reality

The centralization of trust initiated by the Medici reached its absolute zenith in the 20th century with the establishment of the fiat standard. For centuries, even centralized paper ledgers were tethered to physical reality by a peg to precious metals (the Gold Standard). A paper banknote was legally a claim check on a fixed amount of gold held in a vault, constraining the ability of the issuer to inflate the supply.

The Nixon Shock: This tether was famously severed on August 15, 1971, by U.S. President Richard Nixon. Faced with rising domestic inflation, the costs of the Vietnam War, and a run on U.S. gold reserves by foreign nations, Nixon unilaterally suspended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. This event, known as the Nixon Shock, marked the end of the Bretton Woods system and the birth of the modern monetary regime.

Post-1971 Implications: Post-1971, the U.S. dollar—and by extension, the global economy anchored to it—became Fiat currency. The term fiat is Latin for "let it be done" or "it shall be." It signifies money by decree. Its value is not derived from an underlying commodity but solely from trust in the issuing government's stability, military power, and ability to levy taxes.

The implications of this shift were transformative:

Unlimited Elasticity: Without the physical constraint of gold, central banks gained the power to expand the money supply infinitely. This "elasticity" allowed governments to manage economic cycles and bail out failing institutions but removed the discipline of scarcity.

Centralized Control of Value: The purchasing power of every individual's savings became dependent on the monetary policy decisions of a small committee of central bankers. The ledger was no longer just a record of value; it became a tool of macroeconomic engineering.

The Trust Paradox: Critics argue that this decoupling was a fundamental breach of contract—a default on the promise to redeem dollars for gold—that ushered in an era of structural inflation and financialization.

The 2008 Crisis: The Catastrophic Failure of the Hub-and-Spoke Model

The latent vulnerabilities of the centralized, opaque ledger system were violently exposed during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The crisis was not merely a result of bad mortgages; it was a systemic failure of the Hub-and-Spoke trust architecture.

The Crisis Mechanism: Global finance had evolved into a dense network of interconnected balance sheets. Banks had created complex derivatives (Mortgage-Backed Securities, Collateralized Debt Obligations) that obscured the quality of the underlying assets. Because these institutions operated on private, proprietary ledgers, the true state of their solvency was invisible to the market, regulators, and even to each other.

When the housing bubble burst and asset values plummeted, the "Hub-and-Spoke" model turned into an engine of contagion:

Opacity and Contagion: When Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, the lack of transparency meant that no other bank knew who was exposed to Lehman's toxic assets. The "interbank trust" that underpinned the Medici model evaporated instantly.

The Liquidity Freeze: Banks stopped lending to each other because they could not verify the counterparty's ledger. The flow of credit—the lifeblood of the real economy—seized up. The "Hubs" (major banks) had become Single Points of Failure on a systemic scale.

The Bailout: To prevent a total collapse, governments were forced to intervene. They used the "unlimited elasticity" of the fiat system to print trillions of dollars, effectively filling the holes in private bank ledgers with public money.

The Trust Paradox Crystallized: This moment crystalized the Trust Paradox: Society was forced to trust institutions that had proven themselves untrustworthy (via fraud, mismanagement, and greed) simply because they were "Too Big to Fail." The centralized intermediaries had breached their social contract, privatizing gains while socializing losses.

The Shift to Math-Based Trust: The Birth of Blockchain

It is historically significant that the Bitcoin whitepaper was published by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto on October 31, 2008, in the immediate wake of the Lehman Brothers collapse and the onset of the crisis. Bitcoin proposed a radical technological solution to the Trust Paradox: replace the central intermediary with cryptographic proof.

Nakamoto's Innovation: Nakamoto's innovation was not just a new currency; it was a new architecture for the ledger. It combined the best elements of the historical systems analyzed above:

Like the Rai Stones: The ledger is public and distributed across thousands of nodes. Every participant has a copy of the "truth," ensuring resilience and preventing a single point of failure.

Like Tally Sticks: The record is immutable. Instead of wood grain, Bitcoin uses Cryptographic Hash Functions (SHA-256). Each block of transactions is cryptographically linked to the previous one, creating a chain where any attempt to alter a past record would break the mathematical links of the entire history.

Like Medici Bookkeeping: It is a rigorous, triple-entry accounting system (Debit, Credit, and the Blockchain as the immutable auditor), but the auditor is not a person or a bank—it is a protocol.

The Philosophical Shift: This marked the fundamental philosophical shift from Institutional Trust (trusting a bank, a government, or the Medicis) to Programmatic Trust (trusting code, mathematics, and consensus). In this new paradigm, value transfer does not require a "hub." It is Peer-to-Peer, censorship-resistant, and verified by a decentralized consensus mechanism rather than a boardroom decree.

🔑 Key Takeaways

Money is a Ledger Technology: Money has always been a system of accounting, not a physical commodity. Understanding this is fundamental to understanding blockchain.

The Trust Paradox: Centralization creates efficiency but introduces fragility. The 2008 crisis exposed the systemic risks of hub-and-spoke architectures.

Blockchain as Historical Synthesis: Bitcoin and blockchain combine the best elements of historical ledger systems—distributed consensus (Rai stones), immutability (tally sticks), and rigorous accounting (Medici bookkeeping)—but executed through cryptography rather than social or institutional trust.

The Shift to Programmatic Trust: We are moving from trusting institutions to trusting code, mathematics, and consensus mechanisms.

The Foundation for DeFi: This historical foundation is essential for understanding why DeFi represents such a fundamental shift in financial architecture.

📖 Beginner's Corner

If you're new to these concepts:

Don't worry about the technical details yet: Focus on understanding the big picture—how trust has evolved and why blockchain matters.

The key insight: Money has always been about recording who owes what to whom. Blockchain is just a new way to do this that doesn't require trusting a central authority.

Think about the problems: Consider the problems with traditional finance (slow, opaque, requires trust in institutions) and how blockchain might solve them.

Historical context matters: Understanding the evolution helps you appreciate why DeFi is revolutionary, not just "crypto trading."

⚠️ Important Notes

This lesson provides the philosophical and historical foundation for everything that follows. Take time to understand these concepts.

The Trust Paradox is a central theme that will recur throughout the course.

Understanding the hub-and-spoke model helps explain why DeFi protocols are structured differently.

The shift from institutional trust to programmatic trust is the fundamental innovation of blockchain technology.

Next Lesson: In Lesson 2, we'll explore the contemporary financial landscape, comparing TradFi, CeFi, and DeFi to understand where we are today and where DeFi fits in the broader financial ecosystem.

Last updated